William Greaves | Louise Greaves

William Greaves Filmography

BIOGRAPHY

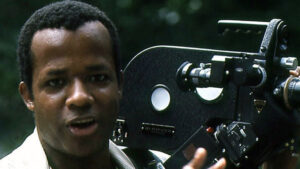

The complex career of William Greaves (1926-2014) remains among the most productive and diverse in the annals of American cultural history. Growing up in a working-class West Indian immigrant family in Harlem as the cultural Renaissance of the 1920’s turned into the long Depression of the 1930’s, Greaves was able to defy social, racial and economic barriers to become one of the most prolific documentary filmmakers of his era.

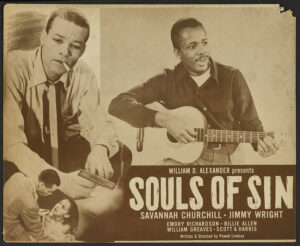

His involvement in the arts began long before he picked up a camera for the first time. By the late 1940s, Greaves was a successful songwriter whose songs were being recorded by major recording artists, a dancer performing with Pearl Primus at Carnegie Hall, and an actor in hit Broadway productions. In 1948 he was accepted into the Actors Studio, where he studied under Daniel Mann, Elia Kazan, and Lee Strasberg. Greaves had featured roles in several of the last independent Black-cast “race movies” in the late 1940’s (The Fight Never Ends, Miracle in Harlem, and Souls of Sin), and in the Hollywood “problem picture,” Lost Boundaries.

His involvement in the arts began long before he picked up a camera for the first time. By the late 1940s, Greaves was a successful songwriter whose songs were being recorded by major recording artists, a dancer performing with Pearl Primus at Carnegie Hall, and an actor in hit Broadway productions. In 1948 he was accepted into the Actors Studio, where he studied under Daniel Mann, Elia Kazan, and Lee Strasberg. Greaves had featured roles in several of the last independent Black-cast “race movies” in the late 1940’s (The Fight Never Ends, Miracle in Harlem, and Souls of Sin), and in the Hollywood “problem picture,” Lost Boundaries.

As to why he made the transition to film production, the best explanation for that comes from Greaves himself:

“I think probably the central reason why I got involved in film production in general and documentary production in particular was that I had the very good fortune of studying African history. That wasn’t something most Black Americans were familiar with back in the 1950s and 1960s. I was fortunate to study with a wonderful teacher, William Leo Hansberry, a professor from Howard University. He was the ranking authority on African history in North America. I became very aware that there was a history of black people that pre-dates slavery. Slavery is the only history that had been taught in America pertaining to blacks; before that, it was assumed we were a bunch of savages running around in the jungle.

I became outraged at the fact that the African-American was misled by the American educational system, by the American media. I became outraged that white Americans were being misinformed about the true nature of who these people of color were. This was a very disturbing experience to me and I said to myself: ‘I should be on the other side of the camera. I should not be in front of the camera, acting and playing various roles, and speaking lines of various authors. Why don’t I get into the production area and tell the truth about people of color?’ I realized that the true story of people of color had not been told. Of course, the documentary was clearly a marvelous instrument by which this story could be conveyed. And I had the good fortune of having read John Grierson’s book, Grierson on Documentary, just about the time that all this ferment was taking place in my thinking, and I said, ‘My God, this is a wonderful, excellent way to pursue a method of consciousness raising, not only among black and white Americans, but among people of all kinds everywhere.’”

Unable to break through the racial barriers in the film industry in the United States, he left the country to train at the National Film Board of Canada. Greaves honed his craft by working in one capacity or another on any and every production he could join. He eventually became chief editor of Unit B, which produced the first cinéma-vérité documentaries in North America, while keeping his lifelong interest in the theater alive by conducting workshops in method acting technique for directors and actors.

After a decade of exile, the opportunity to return home came as racial barriers to employment in the media began to break down under pressure from the early Civil Rights movement. His years of training at the National Film Board of Canada meant that Greaves was well-prepared to capture the historic changes that were taking place across the country. In 1963, together with his wife and lifelong partner Louise Archambault, Greaves moved back to the United States, where they raised their family and he began his long and prolific career as an independent filmmaker.

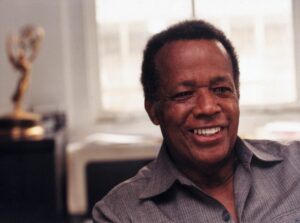

Starting out as a staff producer for the United Nations television, he would then go on to independently produce, write, and direct dozens of award-winning films for public television, educational and governmental institutions and for socially progressive corporate and non-profit organizations, creating a body of work that explored many of the crucial events of the period as well as major figures in African-American history, culture, and politics. In 1970, Greaves was awarded an Emmy for his work as executive producer of NET’s pioneering television series, Black Journal, the first Black-produced series to be nationally broadcast on American television.

From the outset, Greaves was interested in making films that raised consciousness. As he would say later, “I’d rejected the idea of going out to Hollywood. It felt like working out there would be like working on a plantation: you had to answer to the Man for everything you did. We had a different mission.” Greaves did go to Hollywood to executive produce the Richard Pryor/Cecily Tyson comedy Bustin’ Loose. He also incorporated narrative into several of his films, including the Booker T. Washington and Frederick Douglass biographies, but he is known primarily for his documentary work and increasingly for his ground-breaking Symbiopsychotaxiplasm films.

The 52-year filmmaking career of Greaves has resulted in an immense, multi-faceted body of work that includes From These Roots (1974), a poetic evocation of the Harlem Renaissance; Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class (1968), a 90 minute Emmy-nominated special for NET, The Fight (1971), the feature documentary about the championship fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier (a shorter version was released theatrically in 1974 as The Fighters); Nationtime – Gary (1973), the only in-depth documentation of the national Black political convention held in Gary, Indiana in 1972; Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice (1989), an homage to the pioneering African American journalist, anti-lynching crusader and leader in the women’s suffrage movement; Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey (2001), an epic exploration of the contributions of Nobel Laureate Ralph Bunche; and Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One and Take 2 ½ (1971, 2005), two break through feature films that explore the creative process involved in filmmaking, acting and directing; and dozens more films, many of which garnered multiple awards from national and international film festival awards. In 2015, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One was one of the 25 films selected that year to be added to the National Film Registry at the Library of Congress, whose mission is “to ensure the survival, conservation, and increased public availability of America’s film heritage.”

–Adapted from the Preface by Scott MacDonald in William Greaves: Filmmaking as Mission (Columbia University Press, 2021)

AWARDS

In addition to awards for specific films, Greaves also received numerous other awards and honors, beginning with the Russwurm Award in 1970 from the National Association of Black Journalists. In 1980 he was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, and was also the recipient of a special homage at the first Black American Independent Film Festival in Paris. In 1986, Greaves received an “Indy”—the special Life Achievement Award—from the Association of Independent Video and Filmmakers. In 2001, he was honored by the National Black Theater and Film Festival with its first award for Lifelong Achievement in Film and for Contributions to Black Theater. That same year, Greaves also received the Distinguished Documentary Maker Award from the New York Film/Video Council and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Association of Motion Picture and TV Producers. In 2004, the International Documentary Association awarded Greaves their Career Award, and in 2006, he was honored with the Africana Heritage Award from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

In addition to awards for specific films, Greaves also received numerous other awards and honors, beginning with the Russwurm Award in 1970 from the National Association of Black Journalists. In 1980 he was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, and was also the recipient of a special homage at the first Black American Independent Film Festival in Paris. In 1986, Greaves received an “Indy”—the special Life Achievement Award—from the Association of Independent Video and Filmmakers. In 2001, he was honored by the National Black Theater and Film Festival with its first award for Lifelong Achievement in Film and for Contributions to Black Theater. That same year, Greaves also received the Distinguished Documentary Maker Award from the New York Film/Video Council and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Association of Motion Picture and TV Producers. In 2004, the International Documentary Association awarded Greaves their Career Award, and in 2006, he was honored with the Africana Heritage Award from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

VIDEO & RADIO INTERVIEWS

There are also numerous printed interviews with Greaves.

They can be found in various places

on the “Reviews” page.

Madeline Anderson Remembers Bill Greaves – Madeline Anderson remembers her friend and colleague William Greaves at a Memorial Tribute at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. April 30, 2015

Discovering William Greaves

A featurette about the making of the Symbiopsychotaxiplasm films. (Criterion Collection, 2006, 61 minutes)

William Greaves talks with NPR’s Tony Cox about the revival of Symbiopsychotaxiplasm (air date: January 26, 2005.) (No longer available.)

Soderbergh Takes ‘Sequel’ to Theaters : Listen to William Greaves, Steven Soderbergh and Steve Buscemi talk about Symbiopsychotaxiplasm on NPR’s All Things Considered with Pat Dowell (air date: January 23, 2005.)

The Collegium Forum: William Greaves & Audrey Henningham

A discussion with Greaves and actress Audrey Henningham, who appears in Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2½. (Fountainhead, 2004, 59 minutes)

Speaking Freely: William Greaves

Greaves discusses his life and career with a focus on his decisions to make films about Ida B. Wells and Ralph Bunche. (Speaking Freely, 2002, 26 minutes)

The Black Experience in Cinema

A brief history of black cinema featuring interviews with Greaves and filmmaker Robert Townsend. (Turner Classic Movies, perhaps 2002, 6 minutes).

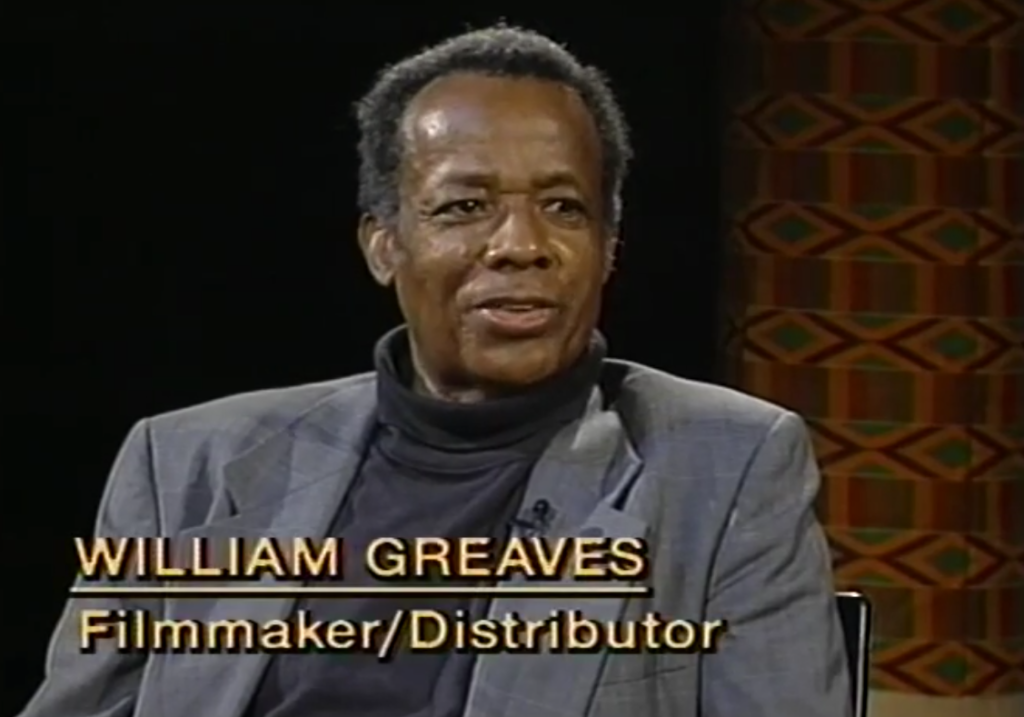

Television in America: An Autobiography – “William Greaves” was episode 8 of the PBS series produced and hosted by Steven Scheuer on PBS. Recorded December 16, 2002.

No longer available online.

Article and three short videos:

William Greaves discusses his film, ‘Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One’

William Greaves discusses his film ‘Voice of La Raza’ and his experience with actor Anthony Quinn

Short excerpts from an interview with Greaves

(The History Makers, perhaps around 2001, 4 minutes & 2 minutes)

African American Legends: William Greaves, Documentary Filmmaker

Greaves talks about his beginning as a filmmaker and his desire to show through images the struggle African Americas have endured. (CUNY TV, 1994, 29 minutes)

MacNeil/Lehrer News Hour, 1991: “New Jack Cinema”

An episode of the ABC nightly news report with journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault interviewing several black directors about the so-called “New Jack Cinema.” Guests included William Greaves, Warrington Hudlin, Reginald Hudlin, Mario van Peebles, Neema Barnette and John Singleton. The show aired on August 16, 1991.

Filmmaker Louise Archambault Greaves, President of William Greaves Productions, Inc., the New York City-based film production and distribution company she co-founded in 1963 with her late husband, has passed at 90. We mourn her passing and honor her extraordinary life and career.

Louise Greaves handled the distribution of William Greaves’ films and worked tirelessly after his death in 2014 to restore key titles and assure his legacy.

The elder of two daughters of Arthur Archambault and Gratia (“Grace”) Chagnon, Louise Archambault was born on October 8, 1932, in the town of Verdun, Quebec, a farming area in Canada’s Richelieu Valley. Arthur Archambault was of Native descent, having been born on a Mohawk reservation. Her father had been a logger, but by the time Louise and her younger sister Suzanne were born, their parents were struggling financially. They moved to the east end of Montreal where other poor families lived. Their fortunes improved slightly when Arthur received a small inheritance from his brother-in-law, enabling him to open a children’s store in 1939. The family lived behind the store.

Louise and Suzanne were sent to a strict and spartan convent school run by the Sœurs des Saints-Noms-de-Jésus-et-de-Marie (Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary). She recalled “wearing black serge clothing and long sleeves, skirts below the knee, black wool stockings, and black Oxford shoes. We looked like we were from another planet.” She told family members that her girlhood preoccupation was to “avoid going to hell. That was my first thought in the morning and my last thought at night.” At seventeen, she graduated with high honors.

While working as a secretary in Montreal, age 23, her friend Shannon Baker persuaded her to attend an acting class where “The Method” was being taught. The instructor was William (“Bill”) Greaves. A fledgling writer/director at the National Film Board of Canada, Bill had been an early member of the Negro Ensemble Company and a student and teacher at the Actors Studio in New York. Bill and Louise married on August 23, 1959, in Montreal, but some of her relatives did not approve and refused to attend the wedding. Their 55-year marriage and filmmaking partnership became one of the great love stories of our time.

After Bill directed Emergency Ward for the National Film Board, he decided to return to the United States and apply his filmmaking skills to the fight for civil rights and racial justice. He and Louise moved to a small apartment near his Harlem birthplace. Starting in 1964, when they formed William Greaves Productions, Louise took an active role in managing the logistics and finances of their productions, and she handled the distribution of their films, filling orders for 16mm prints, then VHS cassettes, then DVDs, up until a few weeks before her death.

She also appeared on-screen in three of their films, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (alongside Shannon Baker, who had first introduced her to Bill), Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2 ½ (again with Shannon Baker), and Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class.

Starting in 2018, Louise oversaw IndieCollect’s 4K restoration of the never-before-released 80-minute version of Nationtime. The only film made about the National Black Political Convention of 1972, it serves as a vital link in the history of Black Power in America. Before its premiere at the Museum of Modern Art in 2020, Louise wrote a brief on-screen introduction to place the restored film in historical context. It was subsequently released nationally by Kino Lorber and made available to M4BL, the Movement for Black Lives. The Kino Lorber Blu-ray edition includes an essay by Leonard N. Moore, author of The Defeat of Black Power: Civil Rights and the National Black Political Convention of 1972.

Restorations of Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One and its 2005 sequel, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2 ½ (the latter financed with the support of Steve Buscemi and Steven Soderbergh), were released by The Criterion Collection / Janus Films in 2006. In 2021, Louise made a new deal with Janus Films to acquire another thirteen films by William Greaves — Wealth of a Nation (1964), The First World Festival of Negro Arts (1966), Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class (1968), In the Company of Men (1969), Voice of La Raza (1972), The Fight: William Greaves Director’s Cut (1973), From These Roots (1974), Just Doin’ It: A Tale of Two Barbershops (1976), Frederick. Douglass: An American Life (1985), Booker T. Washington: The Life and Legacy (1986), Black Power in America: Myth or Reality? (1988), Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice (1989), and Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey (2001) — to be released in a Criterion Collection boxed set. At the time of her death, she was working with Criterion on restoration of the 126-minute Director’s Cut of The Fight. With support from The Film Foundation, this project is being completed in collaboration with the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which holds part of the William & Louise Greaves archive and unique motion picture and sound elements.

The Criterion Collection / Janus Films in 2006. In 2021, Louise made a new deal with Janus Films to acquire another thirteen films by William Greaves — Wealth of a Nation (1964), The First World Festival of Negro Arts (1966), Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class (1968), In the Company of Men (1969), Voice of La Raza (1972), The Fight: William Greaves Director’s Cut (1973), From These Roots (1974), Just Doin’ It: A Tale of Two Barbershops (1976), Frederick. Douglass: An American Life (1985), Booker T. Washington: The Life and Legacy (1986), Black Power in America: Myth or Reality? (1988), Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice (1989), and Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey (2001) — to be released in a Criterion Collection boxed set. At the time of her death, she was working with Criterion on restoration of the 126-minute Director’s Cut of The Fight. With support from The Film Foundation, this project is being completed in collaboration with the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which holds part of the William & Louise Greaves archive and unique motion picture and sound elements.

|

|

|

|

In 2020, in collaboration with filmmaker Su Friedrich, a professor of film at Princeton University, Louise created this robust new website devoted to the work of William Greaves. During 2020 and 2021, she shepherded the writing and publication of a major biography, William Greaves: Filmmaking as Mission edited by Scott MacDonald and Jacqueline Stewart, published by Columbia University Press.

In 2022, Louise obtained a grant from The Ford Foundation to digitize and assemble Memories of the Harlem Renaissance, which Bill had filmed in 16mm in 1972, but was unfinished at the time of his death and which both of them considered the most important film of his career. Bill had gathered the leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance — writers, artists, musicians, feminists and historians, many in their 80s and 90s — at the home of Duke Ellington (then occupied by Ellington’s sister, Ruth). Their extraordinary recollections created a lively and utterly unique audiovisual record of their struggles for recognition and success. This project is now being completed under the supervision of David Greaves and Anne de Mare, in collaboration with BB Optics and the Schomburg Center, with the support of Ford Foundation program officer Jon-Sesrie Goff.

At the time of her death, Louise was also working with the Actors Studio on a tribute to her husband and was organizing William Greaves film retrospectives in the United States and around the world to launch on the centenary of his birth in 2026.

As she checked herself into Sloan Kettering Hospital for a blood transfusion on February 2, Louise emailed a friend, “I have a bunch of projects in the works and not much energy. Keeping my fingers crossed.”

That first blood transfusion energized her. She got herself released and went back to her home office a week later. But the leukemia got the upper hand again. Sharp until the end, she realized her body was going to quit before her job was finished. She died at home on March 4, four months after her 90th birthday. Now it is up to us to continue her and Bill’s legacy.

Louise is survived by her beloved children — daughters Taiyi & Maiya and stepson David Greaves — and many other descendants on both sides of the family, as well as all of us who loved and admired her.

The Hunter Moving Image Alliance, a series at Hunter College to discuss films and videos, had Louise (and Su Friedrich) as guests in April 2021 for a zoom conversation about Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One and other aspects of the Greaves’ film work.

The Hunter Moving Image Alliance, a series at Hunter College to discuss films and videos, had Louise (and Su Friedrich) as guests in April 2021 for a zoom conversation about Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One and other aspects of the Greaves’ film work.

The following filmography lists the films and TV programs that Greaves worked on, and/or acted in, between the mid-1940s and 2005. Individual episodes of Black Journal are not listed; that list can be found on the Black Journal page on the site.

The filmography was assembled by Aurore Spiers (*) for William Greaves: Filmmaking as Mission, due out in 2021 from Columbia University Press.

While the book includes additional technical details and mentions other cast or crew members, this filmography represents a simplified version, with only Greaves’s role, the name of any other director, and the release date of the ninety-one films. (**)

Some entries are marked as “NFB” because many of those are accessible from the National Film Board archives (***).

Titles are listed chronologically, and titles from the same year are listed alphabetically.

We Hold These Truths (actor). [No other information available.]

The Colored Harvest: “America’s Number One Mission Responsibility” (actor). ca. 1946-1952

The Fight Never Ends (actor; dir. Joseph Lerner). 1948

Sepia Cinderella (actor, dir. Arthur H. Leonard). 1947

Miracle in Harlem (actor; dir. Jack Kemp). 1948

Lost Boundaries (actor; dir. Alfred L. Werker). 1949

Souls of Sin (songwriter [“Disappointment Blues” and “Lonesome Blues”], actor; dir. Powell Lindsay). 1949

The Settler (narrator; dir. Bernard Devlin, Raymond Garceau; NFB). 1952

Eye Witness No. 51 (editor; NFB). 1953

Canadian Venture (editor; dir. Caryl Doncaster; NFB). 1956

Forest Fire Suppression (editor; dir. Lawrence Cherry; NFB). 1956

Looking Beyond: Story of a Film Council (editor; dir. Stanley Jackson; NFB). 1957

Putting It Straight: A Story of Crooked Teeth (director, editor; NFB). 1957

Profile of a Problem Drinker (aka David: Profile of a Problem Drinker) (editor; dir. Stanley Jackson; NFB). 1957

Blood and Fire (editor; dir. Terence Macartney-Filgate; NFB). 1958

The Face of the High Arctic (editor; dir. Dalton Muir; NFB). 1958

High Arctic: Life on the Land (editor; dir. Dalton Muir; NFB). 1958

Islands of the Frozen Sea (editor; dir. Dalton Muir, Hugh O’Connor, Strowan Robertson; NFB). 1958

Smoke and Weather (director, writer, editor; NFB). 1958

Stigma (editor; dir. Stanley Jackson; NFB). 1958

Trans-Canada Summer (editor, sound effects; dir. Ronald Dick, Jack Olsen, Jean Palardy; NFB). 1958

Emergency Ward (director, editor; NFB). 1959

Four Religions (director [4th segment on “Christianity”], editor); NFB). 1960

Leadership Discipline: You Have Control (editor; dir. Donald Wilder; NFB). 1960

Cleared for Takeoff (producer, director). 1963

Roads in the Sky (producer, director, editor). 1963

Wealth of a Nation (producer, director, writer, editor, narrator). 1966

The First World Festival of Negro Arts (director, writer, co-cinematographer with Georges Bracher, narrator). 1966

Beauty and Fashions of the Women of Senegal (producer, director, writer, editor). 1967

Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class (co-producer with William B. Branch, director, cinematographer, editor). 1968

Black Journal (executive producer, episodes 3-24, co-host with Lou House [aka Walid Siddiq], episodes 1-24; dir. Stan Lathan). 1968-1970

In the Company of Men (Presented by Newsweek Magazine) (producer, director, co-writer with Jack Godler, editor). 1969

Choice of Destinies (producer, director, writer, editor). 1970

The Job Interview (producer, director, writer, editor). 1970

On Liberty (director of one episode of a dramatic series). 1970

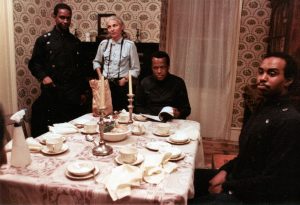

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (co-producer with Manuel Melamed, director, writer, editor, actor). Shot 1968; first edited version, 1971

To Free Their Minds (producer, director, writer, co-editor with David Greaves and Louis De Rochemont III). 1971

On Merit (producer, director, writer, editor). 1972

Struggle for Los Trabajos (producer, director, writer, cinematographer, editor). 1972

Voice of La Raza (producer, director, co-writer with Jose Garcia, co-cinematographer with Jose Garcia, co-editor with John Dandre). 1972

The Fight (producer, director, editor). 1971 [see The Fighters (1973) and Ali, the Fighter (1975)]

The Fighters (producer, director, editor). 1973 [see The Fight (1971) and Ali, the Fighter (1975)]

Childhood Schizophrenia (producer, director, writer, editor). 1973

A Matter of Choice (producer, director, writer, editor). 1973

Nationtime – Gary (producer, director, co-cinematographer with David Greaves and Doug Harris, co-editor with David Greaves). 1972

William Greaves Productions, Inc. originally released this film in two lengths: 80 minutes and 58 minutes. In 2020, Louise Greaves supervised the restoration by IndieCollect of the 80-minute version, which was titled Nationtime.

Power versus the People: A Look at Job Discrimination in Houston (producer, director, editor). 1973.

Someone Who Cares (producer, director, writer, editor). 1973

EEOC Story: A Look at the Work of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (producer, director, writer, cinematographer). 1974

Every Nigger is a Star (cinematographer). 1974

From These Roots: A Review of the “Harlem Renaissance” (producer, director, writer, co-editor with David Greaves). 1974

Whose Standard English? (producer, director, writer, cinematographer, editor). 1974

You’ve Got a Number (producer, director). 1974

Ali, the Fighter (shorter version of Ali/Frazier fight; producer, director, editor). 1975 [see The Fight (1991) and The Fighters (1973)]

A Nation of Visitors (producer, director, writer, editor). 1975

Opportunities in Criminal Justice (producer, director, writer). 1975

The Hard Way (producer, director, writer, editor). 1976

Just Doin’ It: A Tale of Two Barbershops (producer, director, co-writer with Lou Potter, co-cinematographer and co-editor with David Greaves). 1976

The Marijuana Affair (producer, director, co-writer with Woody Robinson, editor). 1976

In Search of Pancho Villa (producer, director, writer, editor). 1978

Where Dreams Come True (producer, director, writer, co-editor with Roger Wyatt). 1979

Your Housing Rights (producer, director, writer, editor). 1979

Gettin’ to Know Me (director [episode 6 “A New Home” and episode 7 “Watusi’s Wall of Respect]). 1980

Bustin’ Loose (executive producer; dir. Oz Scott). 1981

A Piece of the Pie (producer, director, writer, editor). 1981

Space for Women (producer, director, writer). 1981

Booker T. Washington: The Life and the Legacy (co-producer with Billy Jackson, director). 1983

Space for Security (producer, director, writer). 1983

A Plan for All Seasons (producer, director, writer, editor). 1983

No Time for Privacy (producer, director). 1983

Frederick Douglass: An American Life (co-producer with Dwight Williams and Louise Archambault, director, co-writer with Lou Potter, co-editor with Alonzo Speight). Produced for the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in Anacostia, Maryland. 1985

Fighter for Freedom: The Frederick Douglass Story (producer, director, co-writer with Lou Potter). Shorter version adapted from Frederick Douglass: An American Life. 1985

Beyond the Forest (producer, director, writer, editor, narrator). 1986

Black Power in America: Myth… or Reality? (co-producer with Louise Archambault, director, co-writer with Lou Potter, cinematographer, editor, narrator, interviewer). 1986

Golden Goa (producer, director, writer, editor, narrator). 1986

On the Wings of Adversity (producer, director, writer, editor). 1986

Take the Time (producer, director, writer, editor). 1987

The Best of Black Journal (co-host with Lou House [aka Walid Siddiq], executive producer; dir. Robert Wagoner [“Culture in the South”], St. Clair Bourne [“Black Dance”], Kent Garrett [“Modern and African Art”], Horace Jenkins [“Black Beauties and Hairstyles”], Madeleine Anderson [“Malcolm X”]). 1988 [five program segments from NET’s Black Journal (1968-1970)]

The Deep North (producer, director, editor). 1988

Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice (co-producer with Louise Archambault, director, writer). 1989

That’s Black Entertainment (host, co-director with G. William Jones). 1989

Memories of the Group Theater (producer, director). ca. 1990

Resurrections: Paul Robeson (A project conceived and researched, initially for Black Entertainment Television, but never produced). 1990

A Tribute to Jackie Robinson (producer, director). 1990

Spencer Williams: Remembrances of an Early Black Film Pioneer (narrator; dir. Walid Khaldi). 1995

Ralph Bunche: An American Odyssey (executive producer, director, co-writer with Leslie E. Lee, supervising editor). 2001

Television in America: An Autobiography (Episode 8 “William Greaves”: an interview, recorded December 16, 2002). 2002

Ralph Bunche: The Odyssey Continues (director, executive producer, supervising editor). 2003

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2 ½ (co-producer with Louise Archambault Greaves, director, supervising editor). 2005

The 2020 4K digital restoration returns the film to its original 80-minute length and uses a shorter title to distinguish it from earlier versions that were distributed under the title Nationtime, Gary.

(*) Compiling a comprehensive filmography is no small task. Aside from the credit given above to Aurore Spiers, there is a further acknowledgement in the book which bears repeating:

“We thank Nicole Morse for contributions to the early drafts of this filmography. We would also like to thank the archivists and librarians we have contacted and worked with over the years, especially Nancy Spiegel from the University of Chicago Library, Ana Appleyard from the National Film Board of Canada, and the Time-based Media Conservation Team at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Our deepest gratitude goes to Louise Archambault Greaves, whose unwavering support carried us through.”

(**) For anyone interested in a breakdown of the range and amount of Greaves’ work:

There are ninety-one listings in the filmography.

Seven are films in which he acted. On three others, he was either the narrator or the cinematographer of someone else’s film. In one case, he was the executive producer on someone else’s film. And one was an idea that was never produced. (There were many films/episodes done for Black Journal, for which he was executive producer. They aren’t listed here individually, so the larger tally of films that he executive produced isn’t factored in; only the show itself, and the compilation film he did later, are counted.)

In other words, over a fifty-two-year period from 1953-2005, Greaves was the producer, writer, director, cinematographer and/or editor of seventy-nine films.

(***) Availability of the films is not listed, but readers may refer to WorldCat as well as individual library and archive catalogs for many titles listed in this filmography.

Please refer to the Purchase page for information about the 18 films that are featured on the website.

Greaves’ “race films” are available online and/or on DVD, except for The Fight Never Ends (1948).

Almost all the titles produced by the NFB are available in their collections, and some of them are available for streaming on the NFB’s website.

Some works can be found on the American Archive of Public Broadcasting, the Internet Archive, and on YouTube.